The equipment under my immediate supervision today is completely different than what it was 12-15 years ago. To a degree, I miss the transmitter, signal coverage and FCC compliance work. I was trained and have experience specifically in these areas. Over the years, I even became personally acquainted with our friendly neighborhood Detroit area FCC dudes!

Anyone who knows me, knows I thrive on variety. Working on the back-up power generator was not my favorite activity, but I didn’t MIND it. The same for taking a drive for the AM stations to grab "Monitor Points." None of this work was pleasant in the winter months, but it was part of what I did, and sometimes I actually did look forward to “Monitor Points” and listening critically to our station.

The most positive thing about the Chief Engineer’s job was variety. The board operators (a nearly extinct position), would have to endure my wrath when they messed up the log, forgot to take readings or missed the EAS test or an entry in the Tower lighting log. At one station, I was also on-air regularly. That was fun!

When there was a power outage during the winter months, I was always the one who could get the generator going and transfer the equipment over to the back-up circuits WITHOUT FAIL! If the transmitter or station went down for any reason, I could always get things “back,” again WITHOUT FAIL. There was no problem I couldn’t solve, and failure was actually never an option.

In the middle of winter, I once dug up frozen ground to repair a coaxial cable for the satellite receiver. BUT....by the end of the afternoon, we were “back” on the network.

Today, everything is dependant on computers, and while I am not an IT guy, I do have specialized knowledge about the software radio uses. At one time, I could even log in to the transmitter sites of various stations. If they were directional operations, I could verify the operating status of each tower, determine the operating power, transmitter status, and verify the station was “legal.” I no longer have that capability or responsibility, although to a degree, I have it on an automation system from my office.

So what will I be doing in another 15-20 years?

More of the same. I will not be “retired,” I will still be working I hope.

The computers of today will seem primitive

It is hard to predict, but. I will have soaked up much more IT knowledge as it relates to what I do. Perhaps I will have accomplished my lifetime goal, in which case I will be doing even more. AM broadcasting may have become obsolete and that AM knowledge I have will have no use, but all the Programming and audio processing knowledge will have to be unpacked and updated.

“Coverage” may be only a fixed function either of how tall the tower is, or how much bandwidth the audio server can handle.

Change is not always pleasant, or desired. But it is something we can always count on.

TECHNOLOGY THAT IS NOT PERFECTED

By Bob Burnham

I began my career in broadcasting in an analog world. Most of programming at that came from analog tapes, whether in cartridges or from reel to reel tapes. During my on-air years, those inventions had been around twenty or more years and were quite mature.

ANALOG RULED FOR MANY YEARS

Sure, there were issues with them and constant maintenance was necessary to achieve any level of quality and reliability. When we were able to do that, however, the quality and reliability was very high indeed for the standards of that time.

“KIND OF” BETTER

CDs were the first digital medium to come along and suddenly (with a couple of studio CD players) we were supposedly a “digital” station. That wasn’t REALLY true, of course, since the only digital piece of equipment was the player itself which output analog audio into an analog console feeding analog processing to an analog transmitter to analog radios.

But it was “kind of better.” There was no surface noise such as from a vinyl album, or hiss from tape. The recording industry, however, had not YET learned how to make good sounding CDs when they were first invented. Maybe some of us didn’t notice, although purists claimed they could hear the difference and still preferred the sound of vinyl albums to CD.

The broadcast industry did whatever it wanted. The mere convenience of not having to “cue up” a vinyl record or have the cart machine eat the tape seemed to make it worthwhile. As the CD equipment aged, however, we found out that CDs DO skip and sometimes they won’t play at all. That condition worsened when recordable CD equipment became more affordable.

NEW STUDIO PLAYERS A BIG DEAL

But I can assure you at our station, when we got Detroit Radio Legend, Deano Day to do mornings at our station, I got the approval to order bright and shiny new CD players for the main studio. It was kind of a big deal…both Deano and the equipment, that is.

The CD, however, had not been perfected and may never be perfected. Improved upon, yes, but the early claims that a commercially manufactured CD would last “forever” were flawed, and thw CD players themselves have a finite life.

PLAY AUDIO FROM FLOPPY DISC?!

Someone invented various types of digital “cart” players in an attempt to replace the analog carts that had been around since the 1960s.

The most laughable was the version that used computer floppy discs (remember them!?) as the medium. The problem was they could only hold about 2 minutes of audio. Most of us kept using analog carts. I had already developed a knack for re-winding higher grade tape into old cart tapes and replacing any worn parts. Our carts sounded great, and rarely jammed. I felt then, that the broadcast cart format was as good as it was ever going to get.

CONSUMERS HATE MD, BUT RADIO USED THEM ANYWAY

CD recorders were still too expensive. Sony, however, invented the recordable MiniDisc. Although it never caught on with consumers, broadcast stations embraced the format. Sony also manufactured various commercial grade MD players.

Hard drive based systems were still pretty expensive so many stations found they could replace cart machines with MD at a much lower price.

It wasn’t perfection, though. The MD format has inherent problems and limitations, although for the most part, sound wasn’t one of them. Sony got it right in that department, inventing their own proprietary audio compression for MD in 1992. It wasn’t MP3 or any of its predecessors. Sony called it “ATRAC” which stands for Adaptive Transform Acoustic Coding. WHATEVER! It was the key to how they were able to fit 80 minutes of stereo audio into a small optical disc, and still have it sound really good.

NO ESCAPING EVENTUAL FAILURE

Any removable media requiring a mechanical transport, however, will STILL have flaws. In a professional environment, mechanical devices will fail.

Meantime, computer-based hard-drive systems had gradually become more affordable and they became the standard. Stations threw their MD equipment in the dumpster whether it still worked or not.

HARD DRIVE BASED BROADCAST SYSTEMS

The earliest automation systems required a familiarity with Microsoft’s DOS command language. To record a cut, you had to make keyboard entries or hit an F key. Windows based systems and much more studio-friendly touch screens soon replaced the cumbersome early systems during the 1990s. Some of the earliest broadcast automation companies went out of business or were absorbed by the more successful ones,

Like any computer software, automation systems and versions were a constant work in progress. Sometimes version upgrades added many features and fixed problems, but brought along new problems. A stable version meant it could do everything you wanted without crashing or doing something else it wasn’t supposed to.

I wouldn’t say the automation technology is perfected, but it has come a long way in 20 or so years. In terms of reproduction quality, an automation system is capable of SOUNDING better than the tried and true CD format (that was invented in the 1980s).

But like the analog systems of the ancient past, it still needs to be correctly installed AND maintained on an on-going basis.

MECHANICAL PARTS STILL PRONE TO FAILURE

As in any system, the weak link is always the parts of the system that are still mechanical.

In the old days, in an analog cart, if the splice lets go, the tape will spill out into the machine and will appear to “eat” the cart.

In a computer-based system, if there is a hard drive spindle failure, an invading virus or any other kind of hard drive malfunction, the entire system will fail. In the cart machine days, you had only one machine down until the cart tape is replaced and the machine is cleaned. In the computer world, without a level of industrial back-up or redundancy, your station programming is off the air.

HOW PROFESSIONAL SYSTEMS IMPROVE INTEGRITY

In a broadcast world, multiple hard drives in various RAID configurations (Redundant Array of Independent Disks) are used. They spread (or mirror) the data across multiple hard drives. The system will continue to function even if there is an individual drive failure.

RAID technology is used extensively in other fields. There are a lot of other things that CAN go wrong, but this technology has probably reached a reliability level of the venerable cart machine of the analog days.

If one machine (or computer) goes bad in a networked environment, you can generally bring it up on another workstation and be “back” quickly.

The fact is, however, ALL technology is a work in progress. Each advancement whether hardware or software-based will have its positives and negatives. There will always be a way to “break” it or it can “break” itself.

PERSONAL EVOLUTION

My job evolved from the only guy on staff who knew how to load broadcast “carts” (and make them sound almost digital) to that of a multi-purpose digital hardware and audio software guy.

Many factors made my transition a fairly easy one (it was much easier and took a lot fewer years than evolving from a DJ to an Engineer).

DESIGNED & BUILT BY HUMANS BUT WITH CONSTANT NEED FOR ADVANCEMENT

But realize one thing: As advanced as we seem now, what we have is NOT perfected! 10 years from now, today’s hardware will be in the same category as a cart machine is today: Obsolete!

The fact is, however, "cart" machines were built like “tanks” to run forever! If you pulled one out of a dumpster today and plugged it in, it would probably still play. A discarded CD player, however, (with its all-plastic drawer, if it still opened) would probably just sit there and look dumb.

- Bob Burnham

September 24, 2011

On Being a Broadcast Engineer

By Bob Burnham

What leads a semi-normal everyday kid into a lifetime of techie work?

Over the years, I have realized there are actually people who would love to do what I do for a living. People have actually said that to me. The reality is there is actually no way to totally define and understand WHAT I do by people outside the industry. Fact is, it has been a very long and twisty path that led to now. I didn’t take the traditional approach, nor do I take the traditional approach to anything. But that’s me. It might not be you.

That combined with the fact that in 2010, there simply IS no easy or overnight path into Broadcast Engineering unless your family owns a radio station!

The “traditional approach”, however, CAN be a good starter path that can work well to getting on the road. It may include getting some sort of technical degree or formal training. There is no substitute, however, for hands-on experience. If someone won’t give you that hands-on experience, then you have to create your own. I did both. The only path to becoming a GOOD Broadcast Engineer is to gain that experience, and accept the fact you will learn something new every day, will find yourself specializing in certain areas, but you will never learn everything.

Also, be advised there are bigger salaries and greater job security in other technical fields. But if one has embraced the industry as a whole, then perhaps Broadcast Engineering is where you want to be. If you’re in it strictly for money, it might NOT be what you want.

In my case, I went totally overboard as far as practical experience.

I realized, for example, when I was about 12 years old, that a $15 Lafayette Radio battery-powered mixer could actually be turned into a serviceable broadcast console if enough extra switches and gadgets were added.

So what did I do? I ripped the guts out of a perfectly good audio mixer, stuck them into a bigger “box,” with extra buzzers, whistles and even a meter. I also realized that if I ripped the guts out of ANOTHER mixer and added some stereo pots, I could have a stereo console. Simple, right? Well, I was just a kid who had to find out for real. And when the thing actually worked, I was excited!

Those mixers were only 1-transister circuits that ran on a single 9-volt battery. Soon enough, I was duplicating the circuit with better quality components. As a teenager, I ended up building my own audio console from scratch that evolved. Soon, as decent quality op amps become available, I would put more advanced home-brew electronics into my consoles.

Next, I bought Lafayette’s tube type phono oscillator which put a few milliwatts on the AM band. Eventually I got bored with that, but not before a friend and I would spend hours making DJ tapes, and ultimately taking over the student radio station during my senior year of high school.

After those years, in my life, everything became bigger, more powerful and in some cases, more dangerous, but these were all things that led to what I do now…natural curiousity was a big part of it.

Those interests were concurrent to my interests in related areas. “Old-time” radio programming was another area that I stumbled into by accident, hearing old shows being rebroadcast on an area station. This happened in a 2-story “shack” built in my parents backyard. “The Shack” (no relation to today’s Radio Shack stores) was built from surplus construction materials. It had actual shingles, a slanted roof, carpeted interior, intercoms and a radio and speakers built into the walls, all by me!

I had an “air conditioner” that consisted of a discarded phonograph motor with a hand-carved wooden fan blade. A block of ice sat behind the fan. It wasn’t very efficient!

The radio was a junked chassis that someone had thrown out (again tube type). The set was mounted on a home-made panel centrally mounted on the second “floor” of the shack. A carpeted ladder led to a trap door to the second floor.

For the receiver, once I replaced some capacitors, and added fresh tubes I ended up with a high quality receiver that was my connection to the outside world. The programming on the AM band fascinated me back then, and I wanted to be a part of it and would be soon enough. “The Shack” along with countless projects since then would be a key source of my early education.

Thinking back on the programming being aired...

There were no computers for home use at the time, but the Detroit area was rich with some of the best broadcast talent in the prime of their careers. The original WCAR-AM (which is now WDFN the Fan) featured guys like David L. Prince, H.B. Phillips and Warren Pierce. WXYZ-AM by then featured Dick Purtan mornings, then Johnny Randall (and later Tom Bigby), Joe Sasso, Eddie Rogers and Dave Lockhart. WJR was another story altogether.

But the point was I heard them all through trashed equipment that I was able to bring back to life in my own self-created environment.

That was the kind of kid I was, sometimes with a short attention span, but what ever interest grabbed my attention I stuck with it for a very long time.

My first job in radio where I actually got paid was WBRB-AM in Mt. Clemens, Michigan. Leigh Feldsteen (Gilda Radner’s uncle) was the General Manager, and I was his mid-day air talent Monday through Friday. I was the youngest full time staff member, and we played all sorts of Wayne Newton, Frank Sinatra and similar records. I would read the obituaries everyday sponsored by a funeral home, and ladies in their 80s would call me for requests.

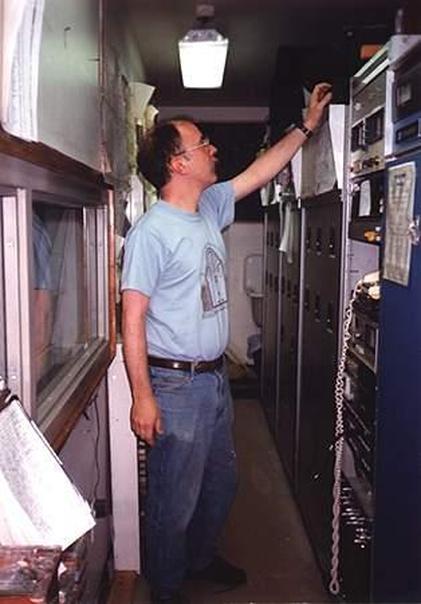

I had to do a lot of remotes from a beat up remote trailer where the air conditioning rarely worked and the equipment was barely functional, however, sport coats and ties were required! One day out of frustration, I found myself re-wiring the trailer. Noticing that, the GM offered me the position of Chief Engineer! Bob Seitz was the regular Chief Engineer at the time, a great guy, but he was well past retirement years.

But I didn't stick around...

Instead, I left WBRB eventually for a gig at Ann Arbor’s WAAM. It was early 1979. There, I would be immediately put to work assisting their Chief Engineer installing new audio consoles as wellas doing all the many remote set-ups with "Fat Bob" Taylor. Taylor would become a good friend.

In the studios, we were the only station in town at the time with slide pots! I would be a full time on-air dude there too, as well as their Production Director. I would have been happy to have worked there indefinitely, but I got too expensive and the industry was changing.

By the end of the 1980s, it was my ability to fix stuff, and install anything under sometimes adverse conditions that would allow me to survive at all in the broadcast industry.

I was in the right place at the right time, and eventually knew all the right people.

There are a lot of people who gave me the incentive or motivation to continue. You really need those kind of people and to feel accountable to someone other than yourself.

Ultimately, you have to WANT to be the best you can be.

For someone outside of the industry, that’s why a place like Specs Howard is so important. The school really has a mixture of the best people in all departments that collectively have created success for both the school and its students under adverse conditions.

You don’t have to be flipping burgers or making minimum wage at a retail store if that’s not what you want. But you do have to do whatever you need to do to create your world, and it doesn’t come overnight. It might not be exactly what you expected, either.

I never had aspirations of being a Broadcast Engineer. It was a means to an end. I would have been happy being that 6-10 nighttime guy on the radio on the AM band. This was both a creative outlet that had a set of responsibilities that went with it that I was very comfortable with. But change is part of the game, and whether even I will always “do what I do” now is unknown. It’s not a perfect world either…but I have to admit it’s a pretty cool one.

If you want a part of it, get out there and start tearing apart equipment and re-building it into something different….or taking what is so obviously someone else’s trash and turning it into serviceable gear. That’s what I did.

-Bob Burnham

4/2/2010

ED COLEBy Bob BurnhamOne of my best friends in both broadcast engineering AND “old-time” radio was H. Edgar “Ed” Cole then of Lakeland, Florida. Barely in his 50s, Ed passed away just a week after the 9/11 tragedy, apparently due to alcohol-induced multiple organ failure and other health problems.Ed worked for many years in central Florida as a broadcast engineer and later did many odd jobs as a cab dispatcher and for that matter, cab driver, until he found less dangerous work tapping into his technical and computer skills. Like myself, Ed was an old-time radio dealer and traded extensively and had many complete runs of more “recent” shows such as the CBS Radio Mystery Theater, Sears Radio Theater, etc. I never got a complete “set” from Ed – just a few samples.One year, Ed and I as a team, worked to record the Friends of Old Time Radio convention in Newark NJ… or reel to reel tapes!During the late 1980s and early 1990s, I visited Ed more than once at his Lakeland apartment and we would always talk radio, equipment, and broadcast engineering almost until morning. In terms of a raw technical theory, Ed could run circles around me, but I had practical hands-on experience. Together we could design, build, program and maintain a broadcast station from the first bolt to flipping the PLATE switch on the transmitter. Ed had a collection of Mitch Miller albums (i.e. vinyl!) that he would have loved to air if given the chance.Although he also had "On-Air" experience, he also held an FCC First Class “ticket” which had been updated to a “General” class license -- something that had been discontinued by the time I was ready to take the test myself. He introduced me to some of his engineering friends in Florida – some of the sharpest people in the business – and we all contributed to each others knowledge and experience in the biz.When people ask how I learned what I know about radio – both past and present – and both the technical and programming aspects, I recall only a few select people like Ed that make up the foundation of people I have been lucky enough to work with.Ed Cole had nothing but a deep-rooted passion for fine-quality sound and what it took to achieve it both at home and at a broadcast station. He had a CD player and a “hi-fi” video deck when that type of equipment was still expensive.Ed was also one of the contributing writers to the books I published mostly in the mid 1980s, “A Technical Guide to Old Time Radio.”(Thank you Friends of Old-Time Radio for the Allen Rockford Award in ’84)Ed and I also briefly co-published a techie trade publication “Radio Forum Newsletter” for the broadcast industry, specifically for engineers. Engineers are not used to paying for anything, however, and it never really went anywhere, but we learned and had fun in the process.Ed had stacks of old Radio World newspapers (a trade publication), and in was in Ed’s stacks that I had first heard of and read the early columns of the Barry Mishkind “the Eclectic Engineer.” Barry (who is now former Radio Guide editor), has an ambitious project , The Broadcasters Desktop Resource www.thebdr.net that is drawing growing attention of those of us out in the trenches. You could say in a sense, Ed introduced me to Barry. Barry IMHO remains one the finest broadcast journalists in the industry today. My best written stuff came through Barry’s guidance, encouragement and expert editing. It’s kind of an indirect and vague connection to Ed Cole, but it’s there, nonetheless, at least in my mind.

Thank you Ed Cole (belatedly) for sharing everything you shared with me.

Me with 1980s-1990s WCAR General Manager, Jack Bailey at a station event.

One of the paths to pursue that reflects an Engineer's success is proving to ALL of the staff that you REALLY are all the same (even if you're not!). You collect a paycheck from the same source but you also work in radio, and for the most part, everyone who works in radio does so because they WANT TO.

Also, when you come in to the station to work your "magic" (and that is what some people on staff consider it), you're better off leading people to think you're a "regular guy" (or girl) the next time a crisis situation arrives and you have to be less-than-friendly, for whatever reason. You'll have many who are both supportive, sympathetic, and maybe even a Program Director who volunteers to go to the transmitter with you, or do some errand for you that will be part of the solution.

Mental Health (i.e. your sanity!) plays a big role in your longevity at the job, your effectiveness to resolve problems and not make serious (or even fatal) mistakes and finally, and to go even farther than you have already gone in the eyes of management.

General Managers are a different breed. The notion that it's lonely at the top may be true in some situations, but most GMs are regular people as well. It's worth the effort to forge an amicable relationship, even if they seem unapproachable.

PROVING IT

I have always had to prove my value to every GM I have ever worked for. It could be a single "working a miracle" event, or many little ones, or simply just being in a good mood amongst the staff and by association, winning him over via the whole staff.

Some GMs have to be EDUCATED about things they need to know. The engineer may have to teach the ones newer on the job simply to be a better GM too if all they REALLY know is how to sell spots. But once you "win" them over it can become a turning point.

When I was Chief Engineer for one of the major groups, I built a talk studio from scratch with a non-existent budget. It was for a new morning show. Everyone seemed to love the new studio, and the GM even circulated a memo among the staff and carbon copied corporate management commending me by name.

Some time later, a successful surprise FCC inspection a week before my last day (the second in my career as Chief Engineer) scored even more brownie points. Despite this, there was low morale at this station for various reasons beyond my control. If I had stayed, however, I could have won the GM over even more, but I had other plans, and sought a situation that was more rewarding.

THE GM IS UNDER PRESSURE, TOO

A GM is constantly being squeezed on both sides by the owner or regional GM who demand a better bottom line, more sales, etc., while the engineer is telling him things that MUST be budgeted for if they are to stay in operation or not be subject to violations, present hazards to the staff, or make it difficult or impossible to remain competitive in the market.

If the GM won't work with the engineer in this respect, even after the engineer has saved the day more than once, it's time for the engineer to look for work elsewhere.

The GM will not be there long with that attitude, but the engineer should not have to tolerate such a situation in the meantime.

GMs with big egos are much bigger challenges, but they are not impossible to conquer -- either they like you or not. If they are neutral, you are still in a good position if you play your cards right.

Any GOOD GM will actively trust and allow the engineer to help him in determining budgetary priorities -- that means realizing and respecting the engineer’s knowledge and experience PLUS treating the engineer with respect so that the engineer actually cares about the station. It is a two way street, but this scenario may not be possible until the engineer has proven himself -- or his prior reputation are evidence enough of his integrity.

BE GOOD NO MATTER WHAT

Some engineers may make it a personal mission to knock the socks off of everyone with a new studio, new on-air sound, or cosmetic things that really don’t cost the company anything extra but are the products of the better engineers.

As it has been mentioned in the past, the feeling of accomplishment once the work is done (and hearing it on the air the next morning) is among the rewards for what might be a particularly tedious task.

The physical appearance of a newly wired rack can also be made to look like a work of art. Only a couple of my colleagues that I have ever worked with share this passion. When you take a photo of such a rack and show it to a non-technical person and compare it to a rats' nest wiring job, it impresses them, particularly when you can do it in the same amount of time as a sloppy "throw it together just so it works" job.

It also demonstrates a certain amount of pride you take in your work. Appearance matters in all respects. They may not understand the purpose of each wire, but when you take a photo "suitable for framing" it sends a positive message to that GM or the PD or whomever you're trying to win over.

Each major accomplishment, such as a completely re-wired rack, should be documented and submitted in a brief bullet-point report either monthly or even better, twice a month. It is not so much a "brag" letter, but a communication tool that gives an effective progress report as well as proving the cost of your salary is a good investment.

If there is a regional engineer, it's also a good idea to CC: him on all such reports. This also serves to align the engineer with the GM in such a way that points out common goals ARE being reached and that you are both on exactly the same team. Again, it verifies the value of the engineer to the station, but especially proves you not just a good engineer, but a detail-oriented engineer who actually cares about the station.

IN THE END, IT'S WORTH THE EXTRA EFFORT

Eventually, a good GM may also reward you with comp tickets to concerts, sporting events, dinners and other freebies he may only share normally with the sales staff.

And yes, he WILL go to the station owner during the holidays and convince the owner to throw an extra hundred bucks or two or three or more in with your holiday paycheck. I have been very lucky in that regard, but nothing came without work and effort on my part.

Doing favors for station clients on personal time, such as duplicating program or spot tapes, helping station clients set up their own studios,

etc., always leaks back to the GM.

If CLIENTS are raving about HIS chief engineer, you can bet when the opportunity comes to reward HIS engineer he will be generous, indeed, even if only in small ways.

"REGULAR" PEOPLE HAVE A BETTER CHANCE OF BEING HIRED

The best GMs have a knack for hiring the best people, but don't necessarily have what it takes to hire the best engineers. One GM had a unique approach: Before I got officially hired, he also asked me to interview with the station’s Contract Engineer (who would later become a good friend and we would share many projects in later years).

Following that second interview (which was more like a swapping horror stories session), I was hired within the next few days.

Additionally, the GM told me, "If I find an engineer more qualified than you, would you agree to let the better engineer have the job, even after the fact?”

I thought that was a nervy question, but I respected his quest to ONLY have the best people work at his station. As it turns out, apparently I WAS quite suitable as I would work for that station for the next 10 years of my life.

Under his direction, we would eventually celebrate the FIRST successful "surprise" FCC inspection of my career and made some long term friends in the process.

HANDLING A "NEW GUY"

There are really only two options if a new GM comes on board who thinks you (or engineers in general) are nothing but a pain and a liability the station has to deal with.

One can either use their best efforts again, to PROVE how good they are or simply quit, or at least get your resume in order, in preparation for that eventual exit.

You already know what you can do, and have the confidence to handle whatever gets thrown your way. You already know how crucial some of your knowledge and ability is to the station operation. You are obviously their insurance policy.

At the same time, while getting your ducks in order, you don't want to flash any kind of an ego in front of anyone at the station, especially the GM.

You just never knew when things could change, or that GM could be your colleague at another facility at another point in your life.

In reality, you want to be a regular person. You respect your current GM's management position, but you're both human. You can probably find common interests, whether it's just enjoying a good steak or more work-related topics such as getting great air sound, or coordinating with programming, a flawless execution of programming elements. This sort of gets back to proving yourself.

If you prove to your GM that they have the best engineer in town for what they want to accomplish, you will be rewarded with the highest salary that the station can support. Whether that salary is sufficient for YOUR needs is a secondary consideration. But that consideration is yours only.

On the management end, a certain maximum dollar figure has been allocated for engineering salaries. That figure generally will never grow if incoming revenue is not growing proportionally. Obviously, it just doesn't make good business sense. Thus, if your Sales Manager doesn't have a good team, or in smaller markets, if the GM is not also a red-hot salesman himself, your salary as an engineer won't grow either no matter how good your relationship is.

But that relationship IS important because it will also help you to solidify your personal reputation. Obviously, that GM has many friends in the industry himself. The outcome could be setting you up for a job for the next 10-20 years; then actually being amongst the first the GM confides to when he decides its time to resign himself (I've actually been in that position!).

When that happens, just repeat the process with a new GM. If the GM is actually the program director you have already forged a good friendship with, then in your life at least, it's business as usual.

As I tell others, I have been lucky most of the time, although I have worked for stations where things weren't so good. Ignoring the "badness", however, and just bringing an upbeat attitude to the situation - no matter how bad it may be -- will always go farther than being an "Oscar the Grouch!"

Being the "Cookie Monster" will always go farther. Who doesn't like cookies and something cold, when faced with the prospect of doing Monitor Points on a directional AM on a humid 90 degree day?

When the staff and GM appreciate what you do, they will buy you all the cookies you want, or at least work a trade-out with a client for you to get a whole case of "something good."

|